That Haunting Style

on Thursday, September, 19 2013 05:04:00 pm , 448 words

Categories: Uncategorized , 46975 views

I LOVE ghost stories! I can't really pin point why I find them so fascinating. I'm sure it must be the folklore aspect, how people morph stories with each telling, each rendition reflecting the interests, values, and tastes of each storyteller.

Likewise, I love history (especially genealogy) and art. Thus architecture for me is a perfect integration of these sundry concerns. Have you ever wondered why we react in certain ways to certain types of art and architecture? Why is it that we have a preconceived notion or pattern of a haunted house for example? Why have once grand edifices built originally for the well-to-do become symbolic in their abandoned and dilapidated state of the gloomy and the foreboding, the haunts of "lost souls"?

Bill Still briefly addressed the basis of this symbolism in his documentary The Secret of Oz (2009), an examination of economic symbolism in L. Frank Baum's children's story The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, explaining that the economic downturns such as the Panic of 1893 left many businessmen, especially rural and small town capitalists, broke. Many of the beautiful homes constructed during the height of the nation's Gilded Age for many such entrepreneurs became a burden, and many were thus abandoned.

Coinciding with the beginnings of the Gilded Age was the birth of the architectural style known as the Second Empire (though today often popularly referred to as early Victorian), in reference to the French Empire during the years of the rule of Louis Napoleon. Developed primarily as an ornate style for the urban structures of Paris, the style caught on and spread throughout Europe in a short time and thence to the Americas. Second Empire style became very popular for imposing governmental structures. Despite the effects of the panics of 1873 and 1893 upon the economy of the United States, many impressive Second Empire style homes have been preserved or restored.

Designed initially for elaborate groupings of structures along bustling city streets, Second Empire structures alone in rural locales seem somehow oddly out-of-place. Especially so were the imposing homes of successful farmers, built during opulence and then suddenly abandoned as a result of economic decline.

Here are a couple online articles that examine the history of Second Empire design and delve into the rationale for our continued impressions of haunted house imagery:

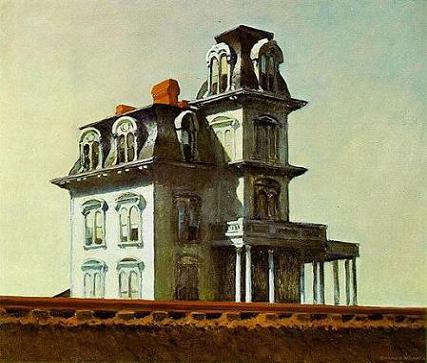

Horror Style: Why Second Empire Scares You by Samuel Scheib and Original Psycho House --- Found by Joel Gunz, both of which contain interesting commentary on Edward Hopper's 1925 painting House by the Railroad, shown here (above).

Illustrations: (Above) American artist Edward Hopper's 1925 painting House by the Railroad. (Below) The Heck-Andrews House, built in 1870 in Raleigh, North Carolina, is representative of the Second Empire style (photo from Wikipedia).