Camels to the American Southwest

on Thursday, October, 01 2020 01:36:00 am , 1418 words

Categories: Uncategorized , 14854 views

In 1836 the Republic of Texas was born. It would last as an independent republic until annexation by the United States of America in 1845, becoming the 28th state upon official induction on December 29 of that year. Also, in 1836, during the Second Seminole War being fought in Florida (our 27th state) between the United States Army and the Seminole, a nation of Native Americans which coalesced in 18th century Spanish Florida of various native peoples, encouragement was given to the U. S. War Department through a substantial study submitted by West Point graduate George Hampden Crosman, an Army officer of the infantry (and, after 1838, of the Quartermaster Department), for the military use of camels as pack animals and proposing the creation of a U. S. Camel Corps. The idea simmered among a limited number of military and government officials for nearly two decades before finally coming to fruition, playing out a chapter in history known variously as the Camel Corps, The Great Camel Experiment, or the Texas Camel Experiment.

Following the Mexican-American War and the 1848 acquisition of a vast (in excess of one-half million square miles) and largely-arid territory known as the Mexican Cession, the expanse of the new territory presented the small 42,000-man US Army the daunting challenge of maintaining the peace, particularly between the regions 100,000 native Americans and the growing multitude of settlers drawn west by the lure of land and gold.

West Point graduate and Army artillery officer Henry Constantine Wayne, a post-war acquaintance of Crosman, conducted further research into the matter and relayed the idea of a camel corps to Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, who twice (1851 and 1852) unsuccessfully introduced the idea of a camel corps in Congressional committee hearings. In 1853 Davis was appointed Secretary of War by President Franklin Pierce, and wrote in his annual report for 1854, "I again invite attention to the advantages to be anticipated from the use of [Bactrian] camels and dromedaries for military and other purposes...." Congress, on March 3, 1855, passed the Shield amendment to the appropriation bill, making $30,000 available for the purchase and importation of the camels.

Major Wayne was selected to lead the buying expedition to Europe, Asia, and Africa. At his disposal was placed the naval store ship USS Supply, Lt. David Dixon Porter commanding. The ship left New York City on June 4, 1855, headed for the Mediterranean. Following examination of camels in London zoos and a visit to Italy to inspect the 250-animal herd of Grand Duke Leopold II, thirty-three camels were purchased in Tunisia (three), Egypt (nine), and Turkey (twenty-one). Also aboard the Supply were saddles and covers, as well as five Arab and Turkish camel drivers, hired primarily because the camels would not respond to commands given in English. The Supply with thirty-three camels aboard (nine dromedaries--one-humped camels, also called Arabians--twenty-three two-humped Bactrians, and one hybrid) left Smyrna, Turkey, on February 11, 1856, and with the addition of a calf born on the eighty-seven day return trip arrived in Texas off Matagorda Bay on April 29, 1856.

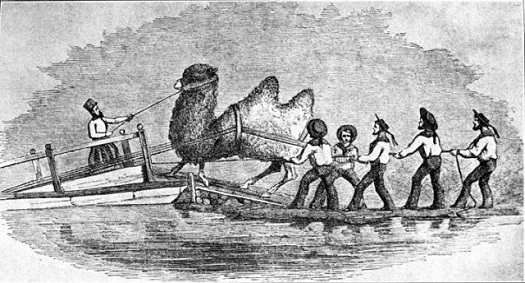

It had been prearranged for a small steamer, the Fashion, to be on hand to take on the camels and carry them over the Pass Cavallo bar to be landed at Powder Horn, later named Indianola (now a ghost town due mainly to its luckless history with Gulf hurricanes). Adverse conditions at Pass Cavallo bar at the mouth of Matagorda bay caused a change in plans.

Both vessels repaired to calm water inside the Southwest Pass at the mouth of the Mississippi River where the Fashion finally received its cargo. On May 14 the vessel again reached Matagorda Bay and the camels were unloaded at Powder Horn. Almost immediately after that event, Lieutenant Porter was ordered by Davis to make a second trip to the Middle East for more animals. Porter sailed before the end of July and returned on January 30, 1857, with 41 camels. By that time five of the original herd had died from disease bringing the numerical strength of the corps to 70. Also accompanying these animal imports were ten additional drivers.

On the 4th of June 1856 Major Wayne moved the caravan of the first group of camels west 120 miles to San Antonio, arriving on the 18th of the month. En route near Victoria, Texas, the animals were clipped and from the pile Mrs. Mary Shirkey knitted a pair of socks to be presented to President Pierce in commemoration of the historic event.

The camel corps was stationed at Camp Verde, Texas, sixty miles north of San Antonio. Major Wayne reported several successful experiments in the region which reflected positive potential utility of the beasts in transport and in the pursuit of Indians. Adult camels, he wrote, could easily rise and walk loaded with as much as 600 pounds (twice what a pack mule could carry), travel vast distance without water, and subsist well on almost any native plants.

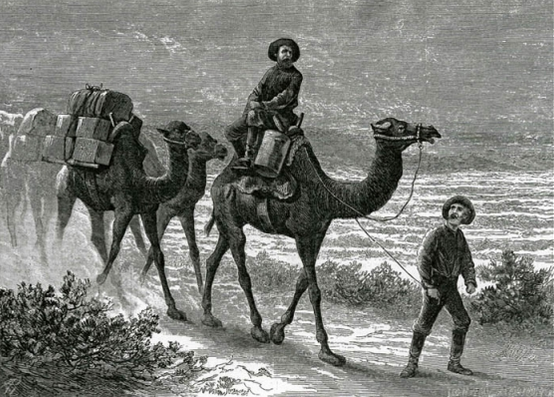

In 1857, a team led by Lt. Edward Fitzgerald Beale (a kinsman of Lt. Porter), made use of twenty five dromedaries as pack camels in their assignment to survey a wagon road from Fort Defiance, New Mexico (now Arizona), across the thirty-fifth parallel to the Colorado River. Fort Defiance was to serve as the base for the expedition to create this wagon road from Kansas to California, which became the basis for the highway Route 66. At one point in the project, on a scouting mission, Beale rode a large white dromedary stallion named Seid for a distance of twenty-seven miles. "The best horse or mule in our camp," he wrote, "could not have performed the same journey in twice the time." From this point, reached on October 17 1857, near Needles, twenty-two animals formed a caravan that continued to Fort Tejon, California, whence the camels were used by the Army for cross desert transport of supplies and dispatches. In early 1858, with about fourteen camels, Beale entered into Los Angeles where a newspaper reported "They [the camels] were found capable of packing one thousand pounds weight apiece and of travelling with their load from thirty to forty miles a day, all the while finding their own feed over an almost barren country. Their drivers say that they will get fat where a jackass would starve to death."

Though highly successful in many aspects the great camel experiment ultimately failed due to the nature of the camels themselves. Though strong, durable, and easily sustained on just about any forage, they were disliked by handlers who were more accustomed to easier-handled (less temperamental) mules. Compared to horses, camels required far more care. The beginning of the Civil War hastened the end to attempts to establish camels as a common mode of transport. Early experiments, even before the arrival of the second load of camels aboard the Supply revealed drawbacks to the military use of camels. They were determined under testing during Major Wayne's leadership of the experiment unsuited for the American manner of combat. They were found, primarily due to size, too unwieldy in close combat, wherein horses were regarded superior. Appropriation requests to Congress in 1858 and 1859 for the purchase of up to 1,000 camels were not acted upon. At the beginning of the Civil War, the Camel Corps was composed of 80 camels at Camp Verde and 31 at Fort Tejon.

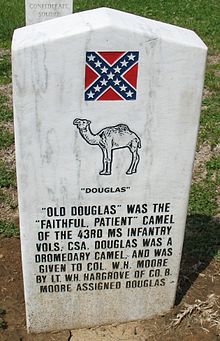

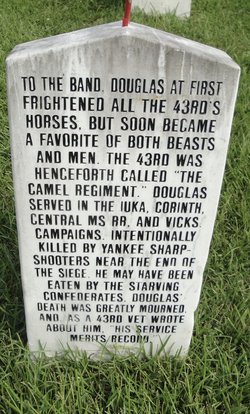

Some of the western group of animals were set free, while others were used to transport salt. Fourteen even returned to Texas after capture by Texas lawyer and Confederate spy Bethel Coopwood. In Texas the Camp Verde camels fell into the hands of the military of the Confederacy. Many of these were turned loose near the fort while others carried bales of cotton to Brownsville. One, known as "Old Douglas," even found his way east where he was used in the war by the command of Captain Sterling Price.

Still regarded as U. S. government property the animals were auctioned off in 1866: sixty-six of them going to Coopwood. In California during the war (1863) some were sold at auction, while others escaped to roam the desert.

On October 16, 1858, a Mrs. M. J. Watson, following the government experiment, reported to Galveston port authorities that her newly arrived ship contained eighty-nine camels which she desired to test for transport suitability. An official, however, averred that she was probably using the camels to mask the odor he claimed to be characteristic of a slave ship and refused her petition to land the cargo. After two months, Mrs. Watson dumped the camels ashore and sailed for the slave markets of Cuba. At Port Lavaca in 1859, a second such private attempt to land camels in Texas was similarly played out.